This present article is a scientific analysis of biotics independently of the regulatory status of the biotics in each member state in EU and does refer to the authorized claim and authorized conditions of use from a regulatory standpoint. The regulatory analysis of the biotics and the claims possible on probiotic has to be made on a case-by-case basis as it is not harmonized at EU level. This regulatory analysis will be the subject of a future article available in RNI newsletter and website.

Definition of biotics

Probiotics refer to “live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host » (FAO/WHO). To be able to be compliant with the definition of probiotic (Hill et al., 2014), the viability of the strain needs to be demonstrated all along the shelf life of the product. The efficacy of the strain must be also demonstrated in the host

Prebiotic is “a substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit”. 3 criteria have to be met for the classification of an ingredient as a prebiotic (Davani-Davari et al., 2019):

- It should be resistant to acidic pH of stomach, cannot be hydrolyzed by mammalian enzymes, and also should not be absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract

- It can be fermented by intestinal microbiota

- The growth and/or activity of the intestinal bacteria can be selectively stimulated by this compound and this process improves host’s health

Postbiotics is a preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host”. The inactivation process, the characterization of the strain, and the validation of the strain have to be described and the health benefit for the host has to be demonstrated. The advantage is the inherent stability of a postbiotic compared to probiotic. The site of action for postbiotics is not limited to the gut: it may be administered at a host surface, such as the oral cavity, gut, skin, urogenital tract or nasopharynx (Salminen et al., 2021).

Synbiotics is « a mixture comprising live microorganisms and substrate(s) selectively utilized by host microorganisms that confers a health benefit on the host”

2 categories of synbiotics (Swanson et al., 2020) exist:

- A ‘synergistic synbiotic’ is a synbiotic in which the substrate is designed to be selectively utilized by the co-administered microorganism(s). The selective utilization of substrate by the co-administered live micro-organism must be demonstrated.

- A ‘complementary synbiotic’ is a synbiotic composed of a probiotic combined with a prebiotic, which is designed to target autochthonous microorganisms. Both must comply with the definitions of a probiotic and a prebiotic.

In any case, the safety, the characterization of the strain, and the health benefit for the host associated to specific conditions of use have to demonstrated and justified.

Specific strain-dependent mechanism of action

Probiotics have several strain-dependent mechanisms of action (Quigley et al., 2019, Zhang et al., 2019):

- Immunological effects: macrophage activation, anti-inflammatory properties, enhancement of NK cell activity, promotion of T helper lymphocyte differentiation

- Actions of digestive health: local pH modulation to reduce pathogen growth, production of bacteriocins and antimicrobial peptides to inhibit pathogen, production of vitamins, stimulation of mucin production, enhancement of intestinal barrier function by reducing intestinal permeability and increase in mucus layer production and tight junctions, SCFA production and transit regulation

They have also a role of the production of neurotransmitters and neurochemicals such as oxytocin, GABA, Serotonin, noradrenaline, dopamine and acetylcholine. They can also modulate the activity of bile salt hydrolase and lactase.

A wide range of clinical benefits that remains strain-dependent

Patients with obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, neurodegenerative disease present a dysbiosis that can be reduced by the administration of probiotics associated to clinical benefits.

Probiotics display several benefits for digestive health. They can reduce antibiotic and C. difficile related diarrhea, may stimulate the immune response, may reduce the severity and duration of acute infectious diarrhea in children. Their consumption is associated to the decrease in abdominal bloating and flatulence in inflammatory bowel disease (Food Supplements Europe, Floch et al., 2017). They may improve digestive symptoms, normalize intestinal transit and reduce constipation. Several meta-analysis confirmed their effectiveness on the induction of remission rate of ulcerative colitis (UC) and the reduction of UC disease activity index with a daily dose range between 1010–1012 CFU/day. Meta-analysis also confirmed their effectiveness for the reduction of total IBS (irritable bowel syndrome) symptoms, flatulence, pain score and bloating score (Chen et al., 2021; Ford et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021).

Several meta-analysis pointed out significant clinical benefits in cardiometabolic health (Da Siva Pontes et al., 2021; Suzumura et al., 2019; Borgeraas et al., 2018; Koutnikova et al., 2019; Dixon et al., 2019)

- Improvement of lipid profile and glycemic control in overweight or obese adults

- Improvement of body composition (BMI, body weight, fat mass, waist circumference) with at least a probiotic dose of 1010 cfu for at least 8 weeks in overweight or obese adults

Clinical benefits were mostly observed with bifidobacteria (Bifidobacterium breve, B. longum), Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus and lactobacilli (Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. casei, L. delbrueckii) and blend of several probiotics.

Probiotics also displays several clinical benefits in cognitive health. They may normalize the anxiety and depression like behavior, may improve cognitive functions in elderly with subjective memory complaints, in Alzheimer disease and patients with mild cognitive impairment (Suganya et al., 2020). Improvement of cognitive functions, behavioral and psychological symptoms in patients with dementia has been observed with a supplementation in probiotics compared to placebo (Pourjafar et al., 2019). More randomized clinical trials (RCT) on the effect of probiotics or synbiotics on Alzheimer, Parkinson patients or cognitive function during aging are necessary to confirm clinical benefits and effective dosage.

Vigilance points during product development with probiotics

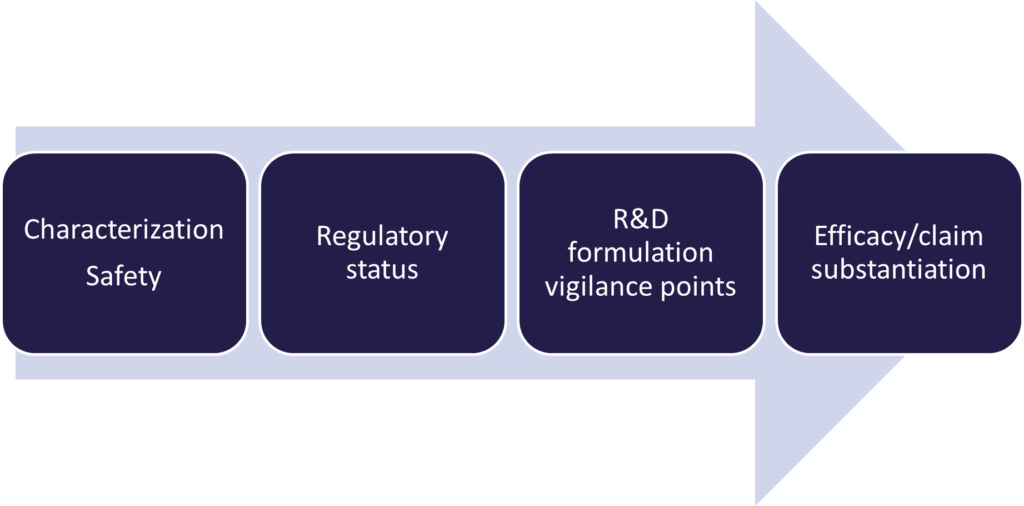

The characterization of the strain with a complete name (genus, species, sub-species) and phenotypic characterization is necessary. The safety assessment is a crucial point including the identification of genes responsible for antibioresistance, and production of toxins. The metabolic activity and side effects noted in humans during clinical trials and during post marketing vigilance has to be carefully studied (WGO Global Guideline Probiotics and prebiotics; EFSA guidance on the characterisation of microorganisms used as feed additives or as production organisms, 2018). The regulatory status (presence in QPS list, novel food risk, the possibility to use the terms “probiotics” in legal denomination name or in health claims…) is different depending on EU member states and constitute a second crucial early step in development.

4 elements have to carefully controlled and assessed during product development:

4 elements have to carefully controlled and assessed during product development:

- The viability of the strain has to be demonstrated during the whole shelf-life. The quantity of the labeling in CFU/g represents the minimal quantity that is guaranteed at the end of the shelf-life. An overdosage is generally applied by the manufacturer.

- The compatibility of the strain with other ingredients in the formula needs to be assessed.

- The stability of the formula

- The protection of the strain during the gastric digestion step may be achieved for example by microencapsulation or the use of enteric capsule for a higher survival rate after the gastric digestion step.

The methodological design of clinical trials with probiotics imply some specificities. The population needs to be representative of the future consumers of the product. A health outcome and a microbiota outcome are necessary. The diet is carefully monitored as it may be source of probiotics and considered as confounding factors. The food supplements and medication are monitored at the recruitment and during the whole study. Recent probiotic, prebiotic, synbiotic or antibiotic use in the last 4 weeks needs to be monitored as inclusion/exclusion criteria and during the whole study.

A clinical benefit to the host needs to be demonstrated through a main outcome that represent a direct health benefit which is specific such as reduction on infection rate, the severity, frequency or duration of symptoms in respiratory tract infection or digestive symptoms for example. Outcome variables which do not refer to a benefit for specific functions of the body cannot be used for the scientific substantiation of a health claim on probiotics. This stipulation covers changes in the following: The composition of the gut microbiota, Immune markers and markers of inflammation, Microbial metabolites (short-chain fatty acid production), The structure of the intestinal epithelium. These parameters refer to a mechanism of action more than a clinical benefit (Food Supplements Europe, Probiotics: growing science and need for proper consumer communication on probiotic food supplements, April 2021).

The international scientific association for probiotics published a consensus on the scientific requirements for claims on probiotics. To be able to claim “contains probiotics” the safety needs to be assessed as a pre-requirement. The viability of the strain. RCT (randomized Controlled Trials), observational studies, systematic reviews or meta-analysis may be used to support the observed general health benefit for the taxonomical category. The efficacy does not have to be generated for the specific strain included in the probiotics.

A specific health claim (digestive health, immune health…) requires:

- Safety data

- Proof of viability for probiotics

- Convincing evidence needed for specific strain(s) or strain combination in the specified health indicatio Such evidence includes well-conducted studies in humans: positive meta-analyses on specific strain(s) or strain combinations, or strong evidence from large observational studies or well conduced RCT. Well-designed observational studies are useful to detect the effect of foods on health in ‘real life’, outside the controlled environment of a RCT

What makes a “good probiotic”?

- Characterization: It is correctly identified (genus, species and strain): choose a probiotic whose strain(s) have been studied and whose effects have been demonstrated.

- Safety/ Traceability: completely safe for the consumer and the environment (QPS or GRAS approach). Established according to standardized processes that ensure the safety of the consumer, guarantee the registration of the product and a post-marketing vigilance after commercialization

- Stability: it guarantees the viability of the probiotic in the ambient environment (temperature/humidity) over time, under normal storage conditions, based on characteristics of the strain, the choice of ingredients used in the composition of the probiotic, and packaging that protects against air and humidity, preferably blister packs or capsules.

- Gastro-resistance tested: able to withstand storage conditions and gastric acidity to remain alive in the digestive tract to be efficient.

- Adhesion to the intestinal mucosa: If its ability to bind to the cells of the intestine is satisfactory, the time that the probiotic strains remain in the intestine will be increased.

- Proven health benefit: Identified mechanism of action, clearly demonstrated clinical benefits, strain and dose effect dependent analyzed in the target population

Probiotics constitute a market opportunity in several product categories: food supplements, drug, FSMP (Food for Special Medical Purpose) for a wide range of target population segments: IBD/IBS patients, obese, overweight people, sport and athletes, aging population, general population and children for immune health, digestive comfort, antibiotics use, respiratory infections.

RNI can help at each step of your product development with a team of regulatory consultants, toxicologist and scientific consultants based in France, UK and in the USA.

Contact name:

Veronique Traynard (PhD), scientific and regulatory consultant

Mail: v.traynard@rni-conseil.com

Mobile: +33 (0)6.71.32.52.97

References :

Davani-Davari et al., 2019, Prebiotics: Definition, Types, Sources, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications, Foods 2019, 8, 92; doi:10.3390/foods8030092

Hill et al., 2014, The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic, Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 506–514

Salminen et al., 2021, The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics, Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 18:649-667

Swanson et al., 2020, The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of synbiotics, nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 17:687-701

World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines Probiotics and prebiotics February 2017 Quigley et al., Prebiotics and Probiotics in Digestive health, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2019, 17(2):333-344

Zhang et al., Interactions between Intestinal Microflora/Probiotics and the Immune System, BioMed Research International , 1-5

Food Supplements Europe, Probiotics: growing science and need for proper consumer communication on probiotic food supplements, April 2021

Floch M, The Role of Prebiotics and Probiotics in Gastrointestinal Disease, 2017, Gastroenterol Clin N Am, 47(1):179-191

Chen et al., Efficacy and safety of probiotics in the induction and maintenance of inflammatory bowel disease remission: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Ann Palliat Med 2021;10(11):11821-11829

Ford et al., Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics and antibiotics in irritable bowel syndrome; 2018, Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 48 (10). pp. 1044-1060

Sun et al., Efficacy and safety of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta‑analysis, 2019, Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology, 26(2):66-77

Zhang et al., Clinical efects and gut microbiota changes of using probiotics, prebiotics or synbiotics in infammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta‑analysis, 2021, European Journal of Nutrition https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-021-02503-5

Da silva pontes, Effects of probiotics on body adiposity and cardiovascular risk markers in individuals with overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, Clinical Nutrition 40 (2021) 4915-4931

Suzumura et al., Effects of oral supplementation with probiotics or synbiotics in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and metaanalyses of randomized trials, Nutrition ReviewsVR Vol. 77(6):430–450

Borgeraas et al., Effects of probiotics on body weight, body mass index, fat mass and fat percentage in subjects with overweight or obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, 2018, Obesity Reviews, 19(2):219-232

Koutnikova et al., Impact of bacterial probiotics on obesity, diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease related variables: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials, BMJ Open 2019;9:e017995

Dixon et al., Efficacy of Probiotics in Patients of Cardiovascular Disease Risk: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, Current Hypertension Reports, 22:74

Suganya & Koo, Gut–Brain Axis: Role of Gut Microbiota on Neurological Disorders and How Probiotics/Prebiotics Beneficially Modulate Microbial and Immune Pathways to Improve Brain Functions, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7551

Pourjafar & Ansari, The Effects of Prebiotics and Probiotics on Mental Disorders, chapter 4, Functional Foods and Mental Health, 2019, p72-90

Publication on July 19th 2022